|

by Jack Walraven © Copyright 2004 Jack Walraven, All Rights Reserved. Warning! Some segments in this document are inappropriate for children. VUNG TAU, JANUARY 1966 As we dropped anchor in the sheltered waters of Vung Tau, it seemed eerily quiet. The surrounding deep green hills, the beached fishing vessels with their nets hung out to dry under the warm blue sky, released some of the tension we had all felt since learning that we were going to Vietnam. Little did we know that our floating home, a 20,000-ton merchant ship flying the Norwegian flag, would find its final resting place some ninety miles up the Saigon river. POSTWAR HOLLAND, 1952 On a dark, gloomy Sunday in 1952, we took the train from Den Haag (The Hague) to Rotterdam. We were on our way to visit Opa Walraven, who was only months away from going blind altogether. Oma Walraven had died earlier in the year when they were still living in Den Haag. It was the only time I ever saw Papa cry. After the funeral, Opa moved back to Rotterdam where he was born. The city was quickly rebuilding but many of the structures were still in ruins and there were large city blocks that stood empty -- testimonial to the severe bombardment the city had suffered in 1940. We sat quietly in the small oppressive sitting room while Opa Walraven talked of the war and the suffering Oma had endured. I didn't understand the words he was saying, except that it had something to do with the destroyed buildings. That night, after being safely tucked into bed, I had my first nightmare, at least the first one I can remember. I was looking at the skyline of an unknown city. Even though it was night, the sky was alit with bright flashes everywhere. Strangely, there was no sound. When I woke up screaming in fear, Mama came and asked me what was wrong. I couldn't find the words to tell her. When the sobbing had subsided, she kissed me gently, turned off the light, and closed the door softly behind her. I've had that dream many times since.

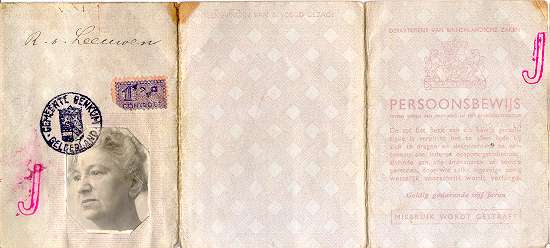

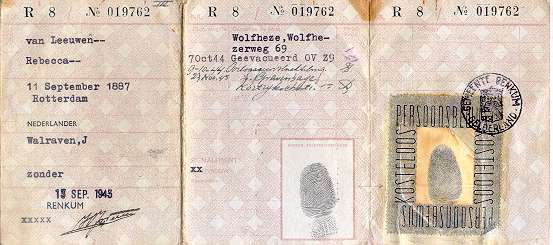

She was born Rebecca van Leeuwen in Rotterdam on September 11, 1887. Her persoonsbewijs (internal passport) reveals part of her story. In 1941, Artur Seyss-Inquart, Reichskommissar for the Occupied Netherlands and highly regarded by Hitler, ordered that all citizens 15 years or older be issued persoonsbewijzen, and that all Jews had to be registered. Persoonsbewijzen had to be carried at all times and there were heavy penalties for not having one. Rebecca's persoonsbewijs was issued in 1943 in the village of Renkum near Arnhem. I never learned of her whereabouts prior to that date and one could only imagine. The first thing that stands out on the card is the big J stamped just to the left of her photo and on the front. That mark turned out to be a death sentence for most Dutch Jews. Those with mixed racial blood, partial Jews or bastard-Jews as the Nazis called them, had either a B-1 or B-2 stamp on their persoonsbewijs, depending on how many Jewish grandparents they had. Traditionally, a person is formally either Jewish or not, but the Nazis sought to divide the whole world of the partially Jewish artificially by counting the number of Jewish grandparents. The "Nuremberg Laws" of 1935 dictated that: 1) three or four Jewish grandparents made one a "Jew," regardless of one's own religion; 2) two Jewish grandparents resulted in a Mischling ('half-breed') First Grade; 3) a single Jewish grandparent defined the Mischling Second Grade; 4) an individual without any Jewish grandparent was to be considered "German" (Aryan).

To the Dutch, this period was one of the bitterest disappointments of the German occupation. Liberation had seemed so close. The area south of Arnhem had been freed. If the allies had succeeded to cross the Rhine, the whole country would have been liberated in a matter of days. Instead, it would take almost eight more months to accomplish this.

If it hadn't been for the farmers outside the cities, many more would have died from starvation. The farmers weren't necessarily altruistic, however, and often traded food for the last few valuables the starving families possessed. Mama had been active in the resistance and her main function was to smuggle food through the German checkpoints from the country into the city. In the late forties she frequently took me to revisit the farmers who had provided assistance in those needy days. For several years after the war, food and supplies continued to be rationed and I was undernourished. For several months, a farmer offered us room and board. We drank milk straight from the cow and ate chicken and pork from animals that had been slaughtered that day. I'll never forget my anguish when I saw the farmer chop the chicken's head off. He flung the headless chicken to the ground and it started running! At night we slept in a barn with the animals. Hospitality went only so far.

Mama was born Hetty Mulder in Tegal, Java on March 3, 1921, a third generation in a line of colonial families in the Dutch East Indies. She had two younger sisters, Marianne Elizabeth (Jannie) and Johanna Roberta (Robbie). Both her father, Derk Mulder, and maternal grandfather, Johannes Banens, served as officers with the Staatsspoor- en Tramwegen in Nederlandsch-Indië (Dutch Indies State Railways). Her mother, Emi Mulder, was also Java-born. The Dutch Indies were the only home they knew and loved. They lived in a picturesque villa with servants and a summer home in the mountains. Every 6 to 8 years the company men were given an 8-month furlough to visit the Netherlands, the official home country. In 1902, when she was five years old, Emi Mulder visited the Netherlands for the first time on a furlough. This is how she remembered the trip: "We left Java on a steamship (which also carried the overseas mail) on a 4-week long voyage filled with events, each more fantastic than the other -- the ports of strange lands, where you could go ashore and meet people from other races and different customs; beautiful scenery (but not as beautiful as our wonderful East Indies); strange creatures of the sea, brown fish and dolphins that could jump out of the water; sharks of which we could only see the dorsal fins and over which secret tales were told that would make your hair rise. And then came the Suez Canal, it was such a narrow passage between two seas that the ship moved very slowly. On both sides you saw the desert, a sea of sand, and now and then camels and small encampments, and at the end there was Port Said. There, the ship was boarded by magicians who could make little chicks appear from their necks, their ears, and even our clothing. For 10 cents young brown boys would dive off the ship, swim underneath it and reappear on the other side. And then we were in the Mediterranean, where I felt cold for the first time." When they arrived in Holland, she was amazed at how big the people were and to see flowers grow in the grass (they're daisies and buttercups, her mother told her). She had never seen cobblestone streets or heard the clop-clop and rattling sounds of the horse drawn carriages over the cobblestones. The horses were so big and robust compared to the small and skinny ones of the East Indies. She had her first ever checkup at a dentist and had to have a molar removed. She remembered that they gave her a chocolate heart and a small flask of cologne to dry her tears. It was all new and exciting, but she was so happy to return to the idyllic life of the East Indies.

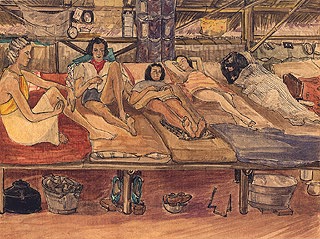

Opa Mulder received a telegram from the railroad company urging him to return to Java. Hetty had decided to become a nurse and wanted to stay in the Netherlands. Jannie was torn but chose to remain as well. Little did they know what was awaiting them and there was a tearful farewell. Oma, Opa and Robbie Mulder boarded a train in Den Haag and, with shuttered blinds covering the windows, they traveled through France to the port of Marseilles where a ship awaited to take them leisurely back to Batavia. (Boarding the ship in Marseilles rather than a Dutch port saved about a week in travelling time to the East Indies.) On May 10, 1940, Holland was invaded and all means of staying in touch were lost immediately. It would be nearly six years before any contact was reestablished. Soon after their return to the East Indies, Opa Mulder took his retirement and they retreated to a mountain villa above Malang to await news from their daughters. Then on December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched their attack on Pearl Harbor and their war machine quickly rolled over Asia, including the Dutch East Indies. On March 8, 1942, the Dutch surrendered the East Indies to the Japanese. "Een zwarte dag! (A black day!)," wrote my grandmother in her diary. Almost overnight the supply of fuel dried up and the busses stopped running. Opa and Oma weren't well prepared because they quickly ran out of food and other daily necessities. All Dutch companies were confiscated and Opa's pension was cut off. They were forced to sell some of their possessions to the Chinese who always seemed to have money. (After the war, when I visited Oma and Opa in their home in Den Haag, I noticed that their attic was always stocked with enough food, water and sundries to supply an army.) In the summer of 1942, the Japanese decreed to move all Caucasians into prison camps -- for their own protection, they said. Men and women were segregated into separate camps. Oma Mulder and Robbie were interred in a camp in Malang, while Opa would spend the next three-and-a-half years away in an unknown men's camp. The Japanese announced the country had been liberated from the Dutch. This basically closed the book on 450 years of Dutch colonial rule over the East Indies. The situation was doubly humiliating to the Dutch prisoners. Oma Mulder wrote that they went from colonials to being colonized in one fell swoop. The idyllic life was over. Initially, in the camp where Oma and Robbie were "housed," there was food, although meager, and the internees were allowed to tend small gardens to grow vegetables. The food situation grew steadily worse and Opa nearly succumbed to starvation in 1945. Dutch cultural activities were strictly forbidden and they were indoctrinated into the rudiments of Japanese society (a society I later came to admire, voluntarily). Oma wrote about the odd trades that were made among the internees. An empty can with a lid was bartered for a package of embroidery thread. Robbie's childhood doll was traded for a whole kilo of sugar. Although the guards were strict, even brutal, they tended to be kind toward the children. Oma thought it remarkable that in times of need, humans could be so creative. The most beautiful things were made with the simplest materials. They got through the day by living out fantasies -- pretending to drink a cup of hot bouillon (lukewarm water) or inventing the most delicious recipes (while consuming the last crumb on their plates).

Indeed. The ultimate irony came on August 15, 1945 when, after the atom bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan surrendered. The war was officially over but no liberators came to bring relief and joy to the prisoners. The allied forced were months away from reaching them. Instead, a new terror appeared in the form of Sukarno and his nationalist forces. Two days after the Japanese capitulation Sukarno issued his declaration of independence. This was a perfect opportunity to get rid of the Dutch once and for all. A power vacuum ensued and whipped into a frenzy by Sukarno and his cohort Hatta, unruly nationalists, guerrillas of various factions, and roving youth gangs declared open season on the Dutch. This was the beginning of a chaotic period known as the Bersiap. The gates to the camps were opened and the internees were free to go, and some did, but it soon became obvious that is was too dangerous to leave. Where could they go? The Japanese were ordered by the allied forces to keep order and protect the internees and after some reluctance, they did. Yet, thousands of Dutch and other Europeans, Indos (Dutch-Indonesians), Amboinese, and Chinese, were killed after the war was officially over. "The only footwear we had in the camp were wooden sandals with a strap that was attached with nails. When the rains came and the grounds around the barracks became soggy, the straps came loose by plodding through the mud. We promised the children a reward if they would search the grounds for replacement nails (they had more freedom to move around)," Oma wrote. "Having no footwear was especially problematic at night when we had to go outside to relieve ourselves. It was painstaking work to clean your muddied feet in the dark before crawling back on top of your mat. We found a solution in an old pot we had brought to the camp (with the illusion that we could use it to do our own cooking). Instead of going outside at night, we used the useless pot as a nachtspiegel (chamber pot)." On the day the war finally ended, the hunger was so intense and the women were briefly able to go outside the camp to purchase some food and cook it themselves. "That night, small pots with simmering contents over charcoal fires could be seen all over the camp. Suddenly, a lady we didn't know walked over to Robbie and I to ask us for a favor. 'I hear that you have a pot that you're not using,' she said, 'Would you mind trading it, because I really want to cook something for myself.' We told her that it had been used for years as a chamber pot. 'I don't care,' she said, 'I'll give you a real chamber pot in return.' And so, from then on we had a real chamber pot, and the lady could happily prepare her soup." While the years in the camp were unpleasant enough for the women, they were spared the violence of the war itself. When the war ended, that reality changed. "We were now confronted with death and destruction by the nationalists," Oma wrote. "It was ordered that anyone caught selling daily necessities to the "whites" would be punished with death. We heard that the families who had left the camps to return to their homes were killed." They eventually left their camp. Oma wrote,"Robbie and I, and many other women, were sitting in a rundown hotel wondering what the future held for us. Some men had left their camps and were reunited with the women. Onze man en vader (Our husband and father) still lay seriously ill from starvation in the hospital of the men's camp in the town we were now in. In the morning, guerrillas came to the hotel, rounded up all the men and took them away in trucks to prison. After the men were gone, several women were frisked for weapons and whipped with bamboo sticks. They were taken away and murdered in the night." "I lay awake that night, knowing that our time was up. Outside, gunshots rang out, intermingled with cries of Merdeka! (freedom) by the guerrillas. Weren't the Japanese -- our former enemy, now that they had lost the war -- weren't they obligated to protect us? But where were they?" "Suddenly, at 4 in the morning, I heard trucks coming our way; heavy boots were marching down the street. Thank God, it's the Japs, I thought. They're jumping out of their trucks to kill the guerrillas. The danger is over. From the kampong across the street echoed more gunshots and cries of Merdeka. The Japanese responded by setting the entire kampong ablaze!" "The following morning the men returned to the hotel from the prison they had been taken. They told us the bloody tale of what had happened. The guerrillas, after killing several Dutch and Japanese, were captured by the "not-so-gentle" Japanese, bound hand and feet, and thrown in the river." Shortly thereafter, a regiment of Ghurkas marched into town. The buildings were quickly cleared from guerrillas and the areas where they were concentrated were bombed from the air. They were indeed out of danger. But, several women camps outside the town had come under mortar fire from the guerrillas. There had been no one to defend them and women and children were losing their lives. The liberated town was ordered evacuated to Batavia in order to make room for the women and children in the beleaguered camps. They would be brought here in camouflaged trucks. "And so, in the morning I received a message -- via a priest -- that I was to take my daughter and immediately join my husband at the men's camp where the former prisoners were in the process of being taken to a departing ship from Batavia. I quickly grabbed my small case (which had long been packed and ready), called Robbie and we were ready to go. But what about the tomato soup? I had just made it! Such delicious aroma and warmth! After all those hunger years, how could I leave it behind? Moments later, we climbed into a Japanese truck (actually, this was forbidden) going in the direction of the men's camp. There stood my husband, impatiently waiting. He said, 'We can just make it on the last truck. Let's hurry!' He paused a moment and said, 'Hey, what are you doing with a pot of tomato soup?' Yes, indeed, what was I doing with it? Away, tomato soup, away. We then jumped on the last truck and we were on our way to the harbor." So finally, in February of 1946 -- sick and miserable, all their possessions gone, but free at last -- Oma, Opa and Robbie boarded a troop ship for the Netherlands. Just before the ship sailed slowly away from the Java coast, Oma got word that Jannie had died. To add insult to injury: Oma -- weighing only 78 pounds and wearing the over-sized trench coat she was given during a brief stop in the Suez Canal -- was accused of being a Japanese spy when the ship arrived in IJmuiden. Opa was carried off on a stretcher. And so began their new life in cold, damp Holland.

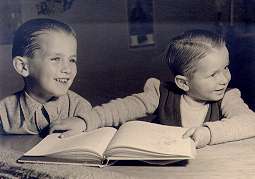

Two Black Roses DEN HAAG, 1957 Since the first grade Tedde Toet and I had been bosom buddies, and for years I had been repeatedly told not to hang out with him. "Jaap has such a wonderful future ahead of him," my second grade teacher told my mother, "but he's so easily influenced. Tedde is leading him up the wrong path." On that first traumatic day of school four years earlier, barely ten minutes after letting go off our mothers' hands, Tedde won the endearment of his classmates and teacher by dipping his tongue in the inkwell. He proudly showed his blackened tongue to everyone, and encouraged by our giggles and cheers, he emptied the remaining ink into his mouth and swallowed it. Twenty minutes later, Tedde was en route to the hospital. We were impressed. Not so the teacher. After six months she asked for a transfer. The more people tried to break up our friendship, the closer we became. What probably scared both teachers and parents was that Tedde appeared so much more mature than his classmates. He was the tallest in the class. His dark skin and wild, black curly hair made him look more ominous than he really was. He was the first one to smoke a cigarette, the first one to drink beer, the first one to sneak into restricted movies, the first one to jump off a building, the first one to do anything. There's only one thing I remember that I did first. At age eleven, I was the first one to smoke a pipe. Tedde was the first one to show me the red-light district of Den Haag. Long after everyone had gone to sleep, we would sneak out of our bedroom windows and walk several miles to the Geleenstraat, where dozens of ladies displayed their wares in dimly lit showcase windows. We would sit on the sidewalk, clad in our pajamas, and time the men going in and out of the narrow doors. Some were only in there for a few minutes. Tedde claimed that he had once seen his own father visiting one of the ladies. I had a big secret that I didn't tell anybody. I was madly in love with Heidi. The movie had affected me deeply, and I somehow identified with her. At night, I would lie in bed and fantasize that Heidi and I had been captured by an evil king. The king's men had tied us up and we were hanging upside down, suspended from the high ceiling in one of the cold dungeons of the castle. Below us were rattlesnakes with slithering tongues. Heidi looked at me with pleading eyes. Although I never figured how to rescue her, or even myself, it was a nice fantasy. Only once did I accidentally blurt out my secret. We were playing "Good Guys versus Bad Guys." Everyone took turns saying who he was. "I'm Roy Rogers," said Lange (Tall) Jaap. I was known as Korte (Short) Jaap at the time. Evie was Lucky Luke. Herman picked the Lone Ranger. Harrie wanted to be Tonto. "And I'm Heidi," I said. All eyes were upon me, dumb-faced. I blushed deeply and quickly changed it to Kuifje.

Although I preferred Kuifje, the most popular comic series in the Netherlands and Belgium at the time was Suske en Wiske -- the wild adventures of a brother and sister and a regular cast of weird characters. First created by Willie Vandersteen in 1946 and published in book form by Standaard Uitgeverij in Antwerp, Belgium, they were originally written in Flemish. I found Kuifje's adventures to be the more intriguing, but Hergé decided to call it quits after two dozen issues. Vandersteen hired assistants to continue his series and today over 200 adventures of Suske en Wiske are in print. I will always consider Hergé and Vandersteen as the world's top creators of a comic series. Occasionally, especially after watching a Gene Autry or Roy Rogers movie in the little community theater on a Saturday afternoon, we would play "Cowboys and Indians." Mostly, however, we played military games. We spent a lot of time in the many small stores that sold military surplus, remnants from the war, where we bought helmets, radio-telephones, and all kinds of other junk. We would then go on maneuvers in the polders, the farm and canal area just outside the city, where we "hijacked" one of the barges used for transporting vegetables. With long poles we pushed the barge through the network of canals. The farms were our battlefields. Hiding the barge in some reeds, we raided the hot houses for grapes and tomatoes. We plucked the trees for apples and pears. We dug up carrots. This wouldn't be any fun if you weren't caught occasionally. The real excitement was when a farmer came out yelling, shotgun in hand, and pumped a blast in our direction. The rush of adrenaline was exhilarating. Now and then one of us got hit by a pellet or two, never too seriously, and that made it all the more realistic. Carrying back our wounded, we called it. Other injuries were getting your skin torn up while trying to escape through barbed wire. Once Evie got his jacket caught in the barbed wire. As the farmer was nearing him, he screamed at us for help. His eyes were filled with the fear of imminent death. Tedde and Herman rushed back and pulled at him with all their might. The jacket ripped apart and Evie was yanked away in the nick of time. I had another hero of sorts at the time, a military one. His name was pilot "Ace" James Bigglesworth of the Royal Air Force (RAF) or "Biggles" for short. The adventures of Biggles take place in the prewar years, WWII, and into the Cold War. In all, 100 books were written. At age 12, I had finally collected half of them. One day, after an unpleasant ending to a game of Stratego, I threw my brother Dick's collection of tin soldiers in the garbage. Dick then proceeded to tear up my Biggles books, one by one. Tedde was going to teach himself how to ride a horse. He wanted to become a cavalryman. Not far from our school was a pasture with several horses. "What you need to do first," said Tedde, "is to befriend the horse. Always approach him from the front. Let him see you." Tedde walked up to the nearest horse, which he called Trigger, and stuck out his hand with some grass in it. "Here Trigger, Trigger. Good boy, good boy..." The horse reared its head, opened its mouth wide and brought it down on Tedde's shoulder. With a fierce grip, Trigger pulled Tedde off the ground and hurled him into the air. Tedde had Trigger's teeth marks for months. End of horse story, except to note that I've been scared of horses ever since. According to Tedde only sissies get involved with girls. That didn't mean that I did not secretly admire some of the girls in my class. I was especially fond of Sylvia and her long ponytail. Only two years earlier, sitting directly behind her, I had dipped that ponytail in the inkwell of my desk, which didn't exactly endear me to her. But now she had become really attractive, a young mixture of Brigitte Bardot and Maria Schell. In drawing class, I drew a picture of her and me naked, in a compromising position, so to speak. All of a sudden I saw Tedde leaning over and he began to snicker. He reached for the drawing and I tried to pull it away. The teacher looked and demanded to know what was happening. Tedde let go off the drawing, but before I could hide it, the teacher demanded to see it. She turned pale and later that evening, she came to our home to talk with my mother. After she left, my mother cried. She had a perverted son, poor Mama. The next day in class, Sylvia kept giving me warm glances. My God, I thought, somebody's told her! All I could do was turn away in embarrassment. But at night, Sylvia replaced Heidi in my dreams. Same fantasy, different girl. Then there was Maria, with hair so red you could spot her a mile away. Often a victim of teasing by other boys, she had a super-crush on me. After school, the Light Tower, as she was called, would ride by my home on her bicycle calling out my name for hours while I cringed in hiding. It finally became so bad that she followed me around everywhere, even when I was with the boys who teased me endlessly about it. "Sailboat loves Light Tower!" they told everyone that would hear. Because of my ears, that was my nickname. I once tried gluing them to the side of my head, but that looked even more ridiculous. "Go away!" I screamed at Maria, "Leave me alone!" But she would just grin at me. "It's not that bad," said Tedde, "Her father is a goldsmith. Pretend that you love her, get as much gold as you can, and then dump her." Tedde always found a silver lining in every cloud. I ended up solving the problem by throwing rocks at her every time she came close to me. Such is love. Probably one of the most hated classes was religion. Not that we hated religion. The teacher, we called him Moses, was right out of the Gestapo. Nearly seven feet tall and with a booming voice, he felt that the only way to teach religion was through fear and intimidation. Child abuse was a virtue with him, and he used the Bible as a lethal weapon, striking people over the head with it. He was a proponent of the "turn the other cheek" ethic. He would bang you across the ear with a giant hand and wait for you to turn the other cheek. Tedde thought that was marvelous. He dared us to use elastic bands or blow pipes, and shoot small projectiles at the bald spot on the back of his head whenever he was writing something on the blackboard. Of course, Tedde was the first one to do that. When Moses let out a yelp, he swirled around and demanded to know who had done it. Tedde, several other boys, and I looked at Willie Wortel, the kid everybody hated because he was the brightest. Moses walked up to Willie and belted him across the head, destroying Willie's glasses. "Turn the other cheek!" bellowed Moses, but Willie just cringed in fear, covering his head with his arms. Moses grabbed one of Willie's ears and began twisting it violently. "Turn the other cheek!" Moses repeated. But Willie couldn't do it, tears streaming down his cheeks. Moses hit Willie's head in full force with the Bible and his shattered glasses went flying across the floor. "Stop it!" yelled Tedde, "Stop it now!" The furious Moses whirled on Tedde, who smiled up at him and pointed at his cheek. Moses slapped him. Tedde, still smiling, turned the other cheek and pointed. Moses slapped him again. "Ah, this feels good," said Tedde, "Hit me again." This continued ten times and although there were tears in his eyes, Tedde never stopped smiling. Finally, Moses stormed out of the classroom in frustration. Tedde and I decided to form our own boys' club, complete with weekly dues and a rule book. As his first lieutenant, I was in charge of collecting the dues and handling all expenditures, which included cheap wine and candles for our clubhouse, a bicycle storage closet in Tedde's basement. Tedde was in charge of drawing up the rules, which were changed every week. He also kept inventing new, sometimes dangerous, initiation rites to test the courage of new members. This included eating live spiders, running through a hailstorm of falling rocks that the other boys had tossed up in the air, and jumping off high places. I remember at least one boy breaking his arm when he jumped down from a second-floor balcony. Probably the most bizarre was to go down to the farms and pee against a fence which had been electrified to keep in the livestock. I was quite relieved to learn later that I was still capable of producing children. Named the Black Spider, the club was patterned after the boy scouts, except that all of the rules were reversed. Instead of a good deed every day, we pledged to do a bad deed every day. One of the rules in Tedde's book: Offer to help an old lady across a busy street. When you get to the middle of the street, run away and leave her stranded. It was all bravado, of course. We never actually intended to do anything cruel, although some of our actions could have caused serious injury or damage. Ever since the second grade, Tedde and I had been designing a rocket that would take us into space. From the contents of firecrackers, we created small prototypes that were fired from a small floating launchpad in the pond of a nearby park. Most misfired, but a few hit heights of up to fifty feet. The reasoning behind the floating launchpad was to provide a "soft" landing zone for future passengers of our rockets. Various insects became our first astronauts. Once, when we had built a fairly large rocket, we tried launching a small field mouse. Unfortunately the thing blew up on the launchpad, frying the poor little mouse. Just like real life. In the summer of 1957, we discovered the bunkers the Germans had built during the war. Tedde had found a fenced-off area called the Waalsdorpervlakte just north of Den Haag. It was an area covering several square miles and consisted of hilly sand dunes, sparsely covered with clumps of reedy grass. Nestled between the sea on one side and a thick forest on the other, it was a remote military installation used for live firing practice.

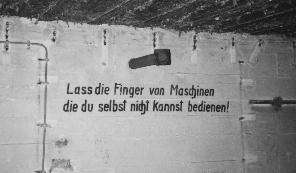

"The bullets themselves are useless," Tedde told me, "It's what's inside the shells that we want." With a small pair of pliers, he gingerly began rotating the bullet inside the shell. "This is an art," Tedde said, "If you force it too much, the thing will explode and blow your hands off." One by one he removed the bullets and emptied the contents of the shells on a sheet of tin foil. We then stored the gunpowder in glass jars. Tedde and I visited the firing ranges and WWII bunkers in the dunes of Den Haag and Wassenaar frequently that summer and the area became our favorite playground. On a couple of occasions, the red flags were up, and crawling through the sand, we heard gun shots echoing through the dunes. Tedde grinned. He loved it. I was afraid that I was going to die. We discovered that the bunkers were part of an extensive network that reached from Hoek van Holland (at the mouth of the Rhine River) in the south to IJmuiden in the north (at the mouth of the IJssel River), a 40-mile stretch of coast facing the North Sea. Den Haag had served as the command center of the German occupation forces. The Germans began building the bunkers in 1942 and were part of the Atlantic Wall, which was erected to prevent allied landings along the coasts of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway. We didn't know it at the time but the Germans had placed over a half million mines in the vicinity of the bunkers. Although many had been cleared after the war, the barbed wire fences and warning signs were obviously an indication that we shouldn't be there. Regardless, we spent the next two years exploring every bunker we could find along the coast. There were said to be hundreds, even thousands, of them in the sand of the dunes. Tunnels often connected the bunkers with various rooms in between.

The ammunition, weapons and other treasures that we found in the sand and bunkers were remnants of the war and we justified our appropriation of these items as archeological exploration. We came upon cases of ammunition, food rations, German magazines and documents, and boxes of the most awful cigarettes known to men. When we smoked a couple, we got so sick that we threw them out. Getting the stuff home and keeping it safe from prying eyes was a problem. We mostly used our bicycles and occasionally took the tram, and stored our caches in secret locations only we had the maps to. Later we included my brother Dick in our search for treasure. He managed to dig up a Nazi helmet, complete with swastika and the skull still inside. When he brought them home (both skull and helmet), Mama had a fit, but she let him keep his prized possessions. Later, an uncle took it all away. The following summer, only nine years old, he went there again on his own. This time he found a "super" bullet -- an intact 18-inch projectile -- weighing over 50 pounds. He tied it to the little rack on the back of his bike and, wobbling with the weight of it, transported it home through the center of city. Mama was not amused when she found Dick in the bedroom we shared, screwdriver in hand, trying to unlock the mysteries of his Super Bullet. I don't remember whatever happened to Dick's Super Bullet, but I think it ended up in Tedde's closet. Tedde had his mind set on finding a V2 rocket. "It's the best rocket in the world," he said. "If I can find one of those, I'll be the toast of the town." Despite my admiration of him, he sometimes appeared off his rocker. Actually, there had been quite a stash of V2s in Den Haag. As of September 1944, the Germans had begun launching these rockets at Britain from the Haagse Bos (Hague Forest) and nearby Wassenaar, causing great damage and terror to the city of London. Over a thousand of them were fired from in and around Den Haag and on March 3, 1945, the Brits finally retaliated and sent a squadron of Spitfires to take out the V2 launching installation in the Haagse Bos. In what came to be known in the Netherlands as the greatest human error of the war, the bombs missed their target and instead flattened Bezuidenhout, a large section inside the city center, killing over 500 residents. It took 50 years before I learned that British bombs and not German ones caused the damaged buildings and flattened areas I had seen in my hometown as a child. Tedde and I used the contents of the shells to make bombs -- a much easier task than building rockets. We put the gunpowder in a can and placed a small flashlight bulb in the powder. The bulb was connected to two long electrical wires. The can was sealed, placed into a hole we had dug in an open field, and then covered with a large rock. Unwinding the spool of wire, we walked back a safe distance to detonate our bomb. It didn't work the first few times when we tried to use simple batteries to set off the gunpowder. But then Tedde brought a small hand-cranked generator he had picked up in a military surplus shop. "Try it," he offered, "Hold this wire in your left hand and the other in your right hand." As he frantically cranked the dynamo, I got a blast that went through my whole body. "Yup, it's working," he said calmly. Tedde had discovered a new initiation rite. It also worked beautifully to detonate our bombs. We blasted rocks into the air to our hearts' content. Finally tiring of looking for ammunition in the dunes, we decided to create our own explosives from scratch. We spent hours going through chemistry books in the library, furiously making notes. Both of our bedrooms were turned into chemistry labs. We burned holes in the floor. We experimented with sulfur and saltpeter. Several times we were chased out of our bedrooms by choking fumes. One night, Tedde blew up half of his bedroom. But our perseverance paid off. We had invented the ultimate explosive. We then did something really stupid, something I still regret today. Across the street from our apartment building the city had just begun operating a tram into the center of the town. "What would happen," I asked Tedde, "if we were to wrap this stuff in tin foil and place it on the track." He shrugged. "Just a big bang, I guess. Let's try and find out." As soon as we placed the foil package on one of the rails, I had a feeling that we had put in too much powder. But there was no time to reconsider, the tram was coming towards us in the distance and we ran for cover. Ding, ding, went the little tram, ding, ding. Then WHAM! One of the steel wheels lifted from the track, and after some loud screeching and sparks, the tram came to a halt. We had derailed it! It was the first time for me to see Tedde scared out of his wits. Two ten-year old little terrorists! I thank God that no one was hurt in that incident. We weren't caught, and we didn't tell anybody about it until years later. Nevertheless, Papa was suspicious and fed up with the mess I was making of my bedroom. In the evening, he packed up all my chemicals and threw them in the canal that ran in front of our building. In the morning there was a crowd of people looking down from the bridge -- looking at hundreds of floating belly-up fish. Way to go, Papa. In the fall, I broke away from Tedde and the Black Spider club and formed my own club, the Red Adder. Our clubhouse was the crawl space below our apartment building. It stretched some 300 feet from one end of the building to the other. The ground consisted of fine sand. In some places, the dry sand was only one foot from the concrete ceiling. In lower areas, the ceiling was up to eight feet high. Here the sand was wet and small lakes had formed. The only way in or out of our clubhouse was through a small opening in the basement of the building. Originally, the opening was covered with a locked wooden cover. It would take six months for anybody to discover that we had removed the lock. Our clubhouse was steeped in total darkness -- the only form of lighting were the candles we brought. The only sounds were from the drain and sewage pipes from the apartments above and the seepage dripping from the ceiling into the puddles and lakes. Whenever we climbed into our clubhouse, we carefully closed the entrance by pulling the cover in behind us. No adult was aware of its existence. Not even Tedde knew where we were. We established our communal space at one end of the crawl space, where it was dry with enough headroom to sit up comfortably. We also had our own initiation rite: crawl to the far wall at the other end of the building, touch the wall, and then crawl back -- all without the aid of a flashlight or candle. The lakes, creepy-crawlies, and the minimal headroom weren't the only obstacles. We also hid some of our "senior" members in strategic places along the way. They were called the "mines." The mines weren't allowed to move, but if you accidentally touched one, you were "dead." Towards the end of December it was neighborhood tradition to collect all the Christmas trees on our street and burn them in a big pile on New Year's Eve. For a one-week period Tedde and I became archenemies. He lived four streets over where the Black Spider boys were collecting trees and hiding them. We stashed ours in our new clubhouse -- the crawl space beneath our building. Black Spider members would launch a sneak attack on a Red Adder member who was dragging a tree down the street, trying to take it away, and vice versa. We battled each other with homemade wooden swords and the lids of garbage cans. It was all in good fun, competing with each other for the biggest bonfire, but sometimes it got rough. Once a boy I didn't know shot me with a pellet gun. It hit me right between the eyes, leaving a red imprint for months. The boy, seeing what he had done, was more shocked than I was. The first day of the year, a truce was declared and we all became friends again. One day we were discovered coming out of our clubhouse by a neighbor. We had been smoking and he was sniffing the air. "What the hell are you kids doing?" he demanded. "Oh, nothing," some of us mumbled. "What do you mean nothing," he said, pointing at his large red nose, "You think I have poop up my nostrils?" Henceforth he was known as Poop-Up-My-Nostrils. When we were in our clubhouse a few days later, we heard a loud banging at the entrance. We quickly doused our candles and listened. Suddenly we saw a light in the distance. Someone had removed the wooden cover. Poop-Up-My-Nostrils poked his head inside. "Are you kids in there? If you are, come right out this minute," he hollered into the darkness. No one stirred. After a moment, he closed the cover. We all sighed with relief, but not for long. We heard banging again, but this time it was much sharper. Poop-Up-My-Nostrils was nailing the cover to the frame! "We are trapped!" cried Herman. Evie started to whine. "Be quiet!" I hushed them. When the hammering stopped a few moments later, I lit one of the candles. All around me were frightened faces. "Nobody knows we're here," Herman said. "We're going to die," said Evie. "Follow me," I said. The reason I wasn't scared is that several weeks earlier Dick and I had been digging outside in the back garden, near the foundation of our building. We had found a spot that led into the crawl space. It was too small to squeeze through, but it would be easy enough to make the hole larger. We covered the hole with a piece of plywood and some earth. Now all I had to do was find it. For two hours, five desperate boys were feeling their way along the back wall of the crawl space. Some were crying again. Our last candle had been used up and the blackness was closing in. I felt a tightness in my throat. I must not panic, I thought. I'm their leader and I'm the only who knows what to look for. If I panic, we will all die. "We must go to the deep area," I said, "Where the lakes are." When we found it there was some relief. At least now we could stand up fully. It was still pitch-dark, however. I needed to think clearly. Our hidden escape route had to be between the bottom of the foundation and the soil below it. I felt my way to the spot where the sand dropped below the foundation and then worked back from there. I could feel the compressed soil below the foundation. There had to be a gap somewhere along the way. Twenty agonizing feet, and then I found it. I stuck my arm through the gap and felt the piece of plywood. There was only a thin layer on top, and the plywood budged easily. The light that entered was blinding, but oh so welcome. We cried tears of joy as we removed enough of the soil to crawl out. We never went back. Which was just as well -- boys in the building behind us had discovered their own crawl space and only weeks after we had abandoned our clubhouse, a fire broke out in the other building. "Stupid boys," we chucked as we stood watching the firemen fight the smoke and flames coming from the crawl space. DEN HAAG, 1960Mama and Papa had divorced. Dick and I had seen it coming, but when it actually happened it was still a shock. I had wanted to go to the same lyceum (secondary school) as Tedde, but Papa had insisted that I attend the venerable Gymnasium Haganum, a highly rated learning institution dating back to the 14th century. In my opinion, it was the stuffiest "snob" school in Den Haag. Papa wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer and all I wanted was to get out of the cradle-to-grave neighborhood we were living in. The moment I walked through the wrought iron gates it felt like entering an asylum housed in a medieval castle, and I knew I didn't belong there. Dressed in blue blazers and grey slacks, my fellow students trudged about like zombies and I was convinced that I was the only one who hadn't undergone a frontal lobotomy. Until I entered Gymnasium Haganum, my school grades had been above average, but with the sudden shift in academic focus they began to suffer -- I immediately stumbled in German and Latin and needed tutoring. Who in the world speaks Latin, I wondered. The following year, with my confidence in learning new languages shattered, I was transferred to a lyceum. Mama had found a condom in my wallet. I was embarrassed, but why did she have to be so hysterical? What was the big deal? Did she think that I was doing you-know-what? The thing had been in my wallet for two years. All the other kids had one, too. Tedde had bought them for us, or more likely, had stolen them from his parents' bedroom. It was a status symbol. I guess Mama felt bad that Papa had never found it necessary to tell me about the birds and the bees. Now he was no longer available. Actually, we occasionally did use condoms. For example, we tied them to the exhaust pipe of our neighbor's car. We also used them as water bombs by throwing them from the fourth floor of our apartment buildings. They made marvelous toys. My only real experience up that point had been with Herman's sisters, both of them. Yvonne, at fifteen, was the oldest, and totally out of my league as a twelve-year old. She hung around the notorious nozems, the Dutch version of the teddyboys of Britain. She was a blonde very much in the image of today's Madonna. Whenever I saw her over at Herman's place, she would tell us little boys all about her sex life. One day she showed us that she was wearing eight panties. "The guys just go crazy when they see that," she said. She was a man-eater. I asked Herman if it would be possible for me to ask his big sister for a date. "I heard that!" Yvonne said. "Would you like to go to a movie?" I asked, nervous to the extreme. "Sure," she said. It must have looked ridiculous. Here's fifteen-year old Yvonne riding her bicycle into the center of the city. And there's me, her twelve-year old "lover," sitting astride on the back of her bike, my arms around her middle, feeling the heat of her belly. We went to see the Guns of Navarone, which, by the way, made me a lifelong fan of Anthony Quinn. On the way back, we stopped by her school, now very dark and abandoned. In the back of the main building she took me into her arms and we kissed, tongues sliding over each other, my first ever kiss. Later we dropped by the local roller skating rink at the Zuiderpark where she promptly abandoned me for her nozem friends. I must be a lousy kisser, I thought, as I walked home alone. Anyway, I did mention that I got "involved" with both of Herman's sisters. The younger one was named Carla and at thirteen she was only a year older than we were. In those days we played a card game called Canasta. We would sit for hours and play the game. Carla, knowing that I had been "broken in" by her sister, would place a nylon-stockinged foot on my lap under the table and probe around. Nobody noticed but they may have wondered why I was slouching so much. When I turned fourteen I began hanging out with a slightly older crowd, kids that rode mopeds instead of bikes. Most of them weren't nozems by any stretch of the imagination and rarely got in trouble with the law, yet they were rebellious in the way they dressed and styled their hair. And the way they rode their mopeds. The coolest moped in the Netherlands at the time, especially in Den Haag, the Puch -- the uncoolest was the Solex and nobody wanted to be caught dead on one. The Puch with its high handlebars was a symbol of the sixties in Holland, as was the Brylcreem-slicked hair. I wasn't old enough to ride one, so I usually climbed on the back of Lange Jaap's Puch when we rode the streets of Scheveningen or Centrum Den Haag with Boelo, Sim and Muus. At every red light we noisily revved the engine and when it turned green, we blasted off with the front wheel raised high in the air while disdainfully looking back at the cyclists. Doing a "wheelie" was not too comfortable when you were riding on the back, and to the amusement of the cyclists, I frequently fell off. The most dangerous thing we did was to race through the Boekhorststraat in the city's centrum. This was the turf of the nozems and they had weapons -- chains, brass knuckles, and switch blades -- and they weren't afraid to use them. The nozem gangs rode Puchs too, with handlebars raised even higher in the style of Easy Rider. It was a stroke of luck that we never fell into their clutches. By this time I had fashioned myself after my new friends -- hair grown long, slicked down with Brylcreem, a big curl that hung down to my eyes, and a large comb in my pocket. I desperately wanted to ride a Puch on my own but nobody was willing to lend me one. Finally, I borrowed the Solex of a neighbor -- a good learning tool, I thought. The Solex was hardly a bucking bronco. In fact, it was really a bicycle with a small motor that you lowered on top of the front tire once you got up to speed peddling it like a madman. When I thought I got the hang of it, I took off down the bike path along the main road. On the way back, while passing a cyclist, we clipped handle bars and I went flying down the bike path. The cyclist was fine but the left side of my face was scraped clean of skin. It must have looked ridiculous -- a kid looking like James Dean falling off his Solex. After a visit to the clinic, I told my unbelieving friends that I had been captured by Indonesian nozems from Rotterdam who had dragged me down the street tied to their Puchs. I never did get to ride my own Puch. Mama was growing increasingly worried about me and decided to call in Uncle Robert to the rescue. Uncle Robert was married to Aunt Robbie, my mother's younger sister. He was a military man, ram-rod straight, a man who jumped out of airplanes and a master of the martial arts. Uncle Robert decided to start off by telling me about the birds and the bees. "Ladies," he said, "can't control their urges. Therefore, it's up to the man to show restraint. And if you must, if you really must do it, then always use the thing Mama found in your wallet. Is that clear?" "Yes sir!" I almost saluted. Tedde's version of sex had been a lot more enjoyable. It was obvious to everyone that I was suffering from a lack of discipline. Even after transferring from the gymnasium to a lyceum, my school work was still suffering and my truancy record was through the roof. I didn't fit the fold, my mother was told, and she and Uncle Robert decided that I was to move in with his family, where I would learn how to become a gentleman and a scholar. My bedroom consisted of a converted closet in the hallway. "Windows are a waste of time," Uncle Robert said, "They make you daydream." He taught me how to fold my blankets and polish my shoes. "Men are judged by the look of their shoes," he said. We were up at dawn for a three-mile run down the beach, followed by an ice-cold shower. "If you dry yourself quickly and vigorously, you'll never get cold," he said. He took me to his barber to get a crew cut. "Gee, I never knew you had a face," he said, after my long locks were gone. He enrolled me into his judo class, where he could legally beat me up. He took me along to the local bars, where we played billiards and drank beer together. (The legal beer drinking age in Holland at that time was fourteen.) "Some day," he said, "I'll take you to a place that'll really make you a man." Wink-wink. The Cold War was intensifying and according to Uncle Robert, a nuclear holocaust was all but certain. He spent the whole summer digging up his back garden, destroying it in the process. "I don't care about the rest of them, but I'm building the best nuclear bomb shelter in the world," he announced. When it was finished he stocked it with canned food and other essentials. It was actually quite impressive, but I doubted that several layers of plywood would withstand much of a shock, never mind keeping out any radiation. For awhile, we had frequent nightly drills, where without warning Uncle Robert would bang pots and pans and blow whistles. "You have four minutes to get into the shelter," he would yell, "Move your butts! Now!" My aunt didn't think too highly of it, and after several weeks of "Total Readiness At All Times," even Uncle Robert tired of it, resigning himself to the futility of it all. In the early winter, after the first snowfall, the shelter collapsed. Uncle Robert taught me manners and etiquette -- with chivalry ranking high on his list of virtues. "There are exceptions to the ladies-first rule," he told me. "For example, a man always enters a bar before his female escort. Do you know why?" he asked. I shook my head. "If there's a brawl inside, the man will get hit first." There was another exception to the ladies-first rule. "A man always descends the stairs first. Just in case the lady trips, you will soften her landing." Uncle Robert could go on for hours like this. I was enrolled in dance school. "A gentleman should know how to dance," said Uncle Robert. "And by that I mean the Foxtrot, the Waltz, and the Tango. Not that Rock'n'Roll stuff or this new thing, the Twist." Actually, a week earlier I had won a Chubby Checker twist contest. It was fun and easy to do. The Arthur Murray dance studio turned out to be a drag. The girls were plasticky goody-goody-two-shoes. The teacher insisted that except for the hands no body parts could touch. They had shoe prints painted on the floor, showing you exactly where to step. Asinine stuff. One day, after our class was finished and a new one was about to begin, one of the kids in our class dropped several stink bombs on the way out. That summed it up quite well, really. Uncle Robert was a musical man. He played the guitar, the piano, the clarinet and the accordion, and could sing all the popular cowboy songs with a real American accent. His favorite was Red River Valley. He tried to teach me how to play guitar, but I was tone deaf and I was unable to get my hands to do two different things at the same time. (When I brushed my teeth with my right hand, my left hand made the same motion.) I did go to accordion school for a few weeks, but it turned out to be a waste of money. All in all, in the year I spent with Uncle Robert, I came to regard him as a mentor and close friend. He had earned my respect and, hopefully, I had earned his. HILVERSUM, 1962 With rare exception, all Dutch males had to serve two years in the armed forces. Most boys were drafted at age eighteen, but if you wanted to, you could volunteer to enter as young as sixteen. After talking it over with Uncle Robert and getting the government's permission to be accepted before my sixteenth birthday, I joined the Royal Dutch Navy. In the initial interview, I was asked to list three preferences for which I would like to be trained for. I listed naval pilot as my first choice, electrical engineer as my second, and radio operator as my final preference.

Next, I was tested for electrical engineering. Again I did quite well, until I was given a straight piece of copper wire and a pair of pliers. First I was to bend it into triangle, then a square, and finally a circle. I didn't get past the triangle. So I became a radio operator. Only a hearing test was required for that, a test which I passed with flying colors. Basic training took place at Marine Opleidingskamp Hilversum (MOKH), the naval training camp in Hilversum near the city of Utrecht. Uncle Robert had tried to prepare me for what to expect and left me with the advice to "just do what you're told, blend into the woodwork, and nobody will bug you." He was still convinced that the world was facing nuclear calamity, and thought that the navy would be a good place for me to be when it happened. For many of the boys boot camp was a living hell, but I remained determined to stick with it for the three months it took to determine who had the wherewithal to serve aboard Her Royal Majesty's flotilla. Over half were expected to drop out at the end of training, either of their own volition or because they weren't able to live up to the camp's motto of Constantia Et Fide -- With Constancy and Faith. The drill instructors, Marines who had recently returned from combat in the former Dutch New Guinea, were given the responsibility to convert us from mama boys into men -- a task they took on with relish. After the Second World War, in 1949, Indonesia finally gained full independence from the Netherlands, but the Dutch refused to honor Sukarno's claim to West Papua, the western part of New Guinea. The Dutch government contended that the Papuans were ethnically different and that they should be given their own independence and unified with the Australian-controlled part of New Guinea. Thus, they retained their military presence there until late 1962, when the territory came under control of the United Nations. In the intervening years the tension between Indonesia and the Netherlands remained high with scattered clashes. In 1961, Sukarno sent in an invasion force of guerilla fighters and war between the two countries seemed inevitable. It was under these circumstances that I joined the navy and I heaved a sigh of relief when the UN took over later in the year. The first three months we weren't allowed out of camp, although at night we could drink beer with the "real" soldiers in the canteen and listen to the jukebox endlessly playing Cliff Richard, Johnny and the Hurricanes and Fats Domino. After a few weeks, I got on friendly terms with my drill sergeant. Normally a beast during the day, he was relaxed and full of good humor after hours. I think one of the reasons he liked me was because of the picture I was carrying in my wallet. "She is my sister," I told him one evening, "I've written her about you and she's interested in meeting you." Fondling the picture, he grinned from ear to ear. He never got to meet my "sister," because I didn't have a sister. The picture was of an obscure Brigitte Bardot look-alike who never quite made it. Except to provide me with dozens of free beers. The sergeant bragged about how they had removed the rings and gold teeth from the enemy soldiers they had killed in the jungles of New Guinea. "How did you remove the teeth?" I asked. "With my boot," he said. Although I highly doubted these gruesome tales, I played along to humor him. If it were true, it certainly wasn't something to be proud of. "Would you believe that the natives there are still cannibals?" he asked me. That I did believe because I had read about the tribesmen who had eaten a missionary. I wondered if the alleged enemy soldiers that they had killed were hapless cannibals with spears. "You know," he said, "human meat isn't all that bad. When you're hungry and it's a question of survival, well, you know what I mean," "Just don't eat my sister," I told him. That broke him up. "I promise, I promise!" he said, slapping me on the back. Gallows humor. The weapon we trained with was the M-1 Garand rifle of World War II vintage. We were taught to take it apart, clean, oil and polish it, and put it back together -- all with split-second precision. It looked simple but it had an awful lot of parts. Shooting it on the firing range took some getting used to. It was heavy, noisy, had a healthy kickback, and it tended to misfire with part of the clip poking out from the top. But it was very accurate and I managed some pretty high scores in target practice. Often with bayonet mounted, we carried our M-1s everywhere we went -- on the run, over obstacles and through barbed wire, in water, and endless hours on the parade grounds. The bayonet was somewhat of a silly weapon, I thought, and when mounted, it made the rifle unwieldy and even heavier. I hoped that I would never get close enough to an enemy where it would come down to a battle of bayonets. Boot camp was finally over and I had "graduated" near the top of my class. I was military material. Tedde Toet and Uncle Robert had served me well. I brimmed with confidence. Or was it arrogance? It didn't matter. I knew how to row my boat. Decked out in my dress uniform, I took the train to Den Haag. Mama was with friends in Germany and Papa came to meet me at Central Station. He had been dead against me leaving school and joining the navy. Nevertheless, he looked proud when I stepped off the train. After the divorce I had seen little of him and he was anxious to make up for lost time. We walked to the cinema and during intermission he surprised me by buying me a glass of beer. He then added to the surprise when he presented me with a half-pack of cigarettes -- his way of saying that I had come of age. That night he came to my bed, lay down beside me, and for the first time ever, he embraced me and held me tight. I was embarrassed, but it felt good. In the morning he made a Spanish omelette, another first, and asked me if Mama would be interested in getting back together with him. I didn't know. I knew that Papa blamed Uncle Robert for encouraging me to enlist and destroying the dreams he had for me. But once he knew that there was little he could do, he enthusiastically supported me in my decision. Later, at a "show" parade on the flight deck of the aircraft carrier Karel Doorman in Den Helder, he took picture after picture, as I brandished my M-1 Garand with bayonet in pose after pose. I felt sorry for him. He wanted me to be a doctor, preserving life, not killing it. Nevertheless, in the excitement of the moment, he beamed with pride. "That's my son," he told everyone. Poor Papa. I was to be trained as a radio-telegrafist, a radio operator. That was cool, but I was disappointed to learn that for the rest of the year I would be attending classes full-time. I already knew Morse Code and how to wave flags, and didn't see the need for learning how to encrypt and decrypt secret codes. To make matters worse, we had to take regular school subjects as well. What I wanted most was to be assigned to sea-duty and get out of Holland. All the stories I had heard made me hungry to see the world. The golden age of Dutch sailing ships roaming the seven seas was long over, but we still had a sizable fleet -- naval and mercantile -- and going to sea was still a realistic dream for boys my age. Many of my friends had fathers, older brothers, or cousins who were at sea, coming home once a year with trinkets from foreign ports and stories that could keep you spellbound for hours. The Netherlands is such a small country that it was every young boy's dream to leave it for a while and see what the rest of the world was doing. In the early days of colonizing, the Dutch were quite sensitive about the size of their home country. When negotiating with local sovereigns in the massive archipelago of the East Indies, the Dutch were often asked how big the Netherlands were. They would pull out a world globe and casually point to an area from the North Sea to the Urals. In 1602, Prince Maurits invited a delegation of royals from the East Indies to the Netherlands where they were wined and dined. They were then taken for an outing to Fort Grave which had been occupied by Spanish troops led by the Duke of Parma since 1584. They were taken there because just at that time, in a raging battle, Dutch troops were retaking the fort and sending the Spaniards fleeing for their lives. It was a nice show of force and the royals were duly impressed with such a "great country and powerful army." Maps of the Netherlands were not officially allowed in the East Indies until the 19th century. In the summer of 1962, most days were spent in the classroom and at night we were on guard duty at one of the camp's gates or on the occasional military exercise. Guard duty was extremely boring and tiring. We worked in watches of four hours on and four hours off. During the off-hours, we would sleep on a hard cot in the guard house. Return to the barracks was not permitted. Except for very brief periods, you weren't allowed to sit down. The only excitement came when some of the sailors and marines returned to camp roaring drunk, a common occurrence. If they were too drunk or rowdy, we were supposed to lock them up in the brig which usually ended up in a scuffle of some sort. Sometimes we would have ten or more "prisoners," some of them your friends, in the cramped cells. At the end of each watch, we awakened all the inmates and tied their hands behind their backs. We then "aired" them by walking them like dogs on a leash. In the meantime, all the cells were hosed down. The closest we got to water was in the fall, when we spent two months in a sailing camp at a lake near Utrecht. It was mostly rowing and very little sailing. I promptly suffered my one and only "military" injury by slicing off the tip of my finger while cutting bread. One evening we attended a live outdoor concert by Roy Orbison and a Moluccan group named the Diamonds. Cliff Richard did a concert in Rotterdam, but I missed that. At night we roamed the clubs and bars of Utrecht, but since the streets were overcrowded with military personnel, and given the fact that we were still regarded as pipsqueeks, we didn't stand a chance in competing for the ladies. The only romance I felt was in the winter, when I was on leave in Den Haag. A beautiful female singer in a downtown club never took her eyes off me while singing a wonderful love song. Even though the place was filled with several hundred people, she was singing just for me. Wow! Famous singer falls in love with teenage sailor, read tomorrow's headlines. Extra! Extra! Read all about it! The dream was shattered when she picked somebody else for her next song. My naval career came to an abrupt end in March of 1963, when Mama told Dick and I that she was going to marry Bill, a U.S. naval officer she had met in Rotterdam. Bill served on the aircraft carrier Wasp based in Norfolk, Virginia. On an earlier leave, Mama had taken us aboard the Wasp to meet with the jolly rotund Bill, who really wasn't an officer but a chef (okay, he was just a cook). I had worn my uniform and self-consciously compared it to the one worn by the U.S. sailors -- I preferred mine, especially the headgear. Mama told us that we were first going to emigrate to Canada and after their marriage, we would move to the United States. I was gonna be a Yankee-Doodle-Dandy! Whoopee! I was also disappointed, of course, that I would never be a Dutch admiral. I had one final fling with the guys. In honor of my departure, Boelo's older brother Sim had rented a Cadillac convertible for a week. Five of us, all smoking big fat cigars, and decked out in fancy suits and dark glasses, were going to terrorize the streets of Holland. After circling our neighborhood for an hour, loudly honking our horn to make sure everybody saw us, we hit the beaches at Scheveningen and Katwijk, the draw bridges of Delft and Gouda (scraping the undercarriage of the Cadillac), the Walletjes of Amsterdam, the bars in the port of Rotterdam, the cheese market in Haarlem. We attended an amateur rock concert in which some friends of ours were participating. They had called themselves Muus and the Mystics and were making their debut appearance. When they appeared on stage, all dressed in black leather jackets, the crowd cheered. Their first number was Peggy Sue by Buddy Holly. God, they were awful! The cheers turned to boos. Halfway through their second number, they were bombarded by empty Heineken and Amstel bottles, and they never got to finish it. "Ah critics," mused Muus later, "They know nothing about music." A car that size, and a convertible at that, was a rarity in 1963 Holland. Everywhere we went, people stared at us. We spent most of our time standing up in the convertible, twisting and shouting, and waving and cheering at all the lonely people. There were so many new rock bands starting up at that time, that most people simply assumed that we were rock-and-rollers. I mean who else could do something that outrageous. Bill Haley and the Comets? Nah! They're passe. You don't mean the Beatles, do you? Hmmm, could be. That one guy does have a pretty big nose. "Love, love me doooo...," we all sang. See I told you, it's them! Hey guys, it's the Beatles! "Love, love me doooo..." AMERICA, MAY 1963 It was sayonara time. Except for Papa, they were all there -- Uncle Robert and Tante Robbie, Oma and Opa Mulder, uncles and aunts, cousins and nieces and nephews, friends and friends of friends. Some were even crying, waving their handkerchiefs as Holland America's Rijndam moved away from the pier.