|

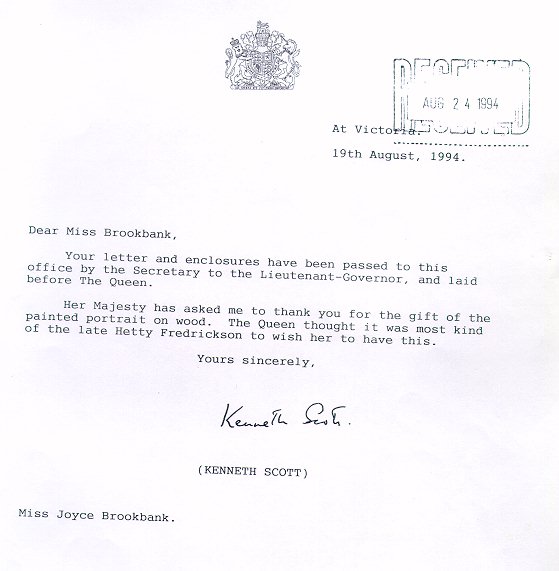

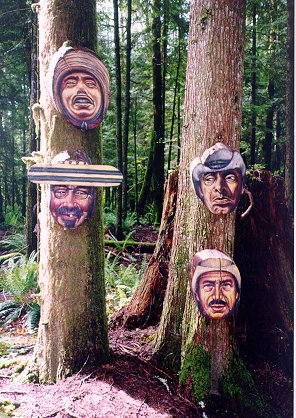

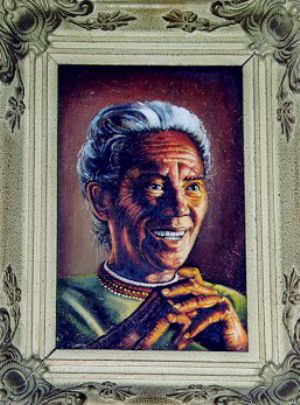

This page (in progress) is in memory of my mother, Hetty Fredrickson, who passed away in 1994. Hetty, an artist, was best-known for her creation of the Valley of 1000 Faces, an outdoor gallery in the forest, which she operated for 25 years on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. |

Hetty Mulder - Fredrickson1921 - 1994 |

|

|

From the moment I was old enough to compare mothers, I knew that my mother was unusual. She stood well over 6 feet tall in her bare feet, a head taller than my father (wearing heels). Some women may feel self-conscious about being so tall, but not my mother. She was proud of her height and she added to her stature with a personality that exuded flair, exuberance, and a wicked sense of humor. Many of the children in our neighborhood -- and some adults -- were convinced that she was a witch and she did nothing to dispel that notion. When my brother and I were asked if we were little wizards, we told them that our mother was not a witch, she was the Queen of Sheba. So, here's the story of Hetty, the Queen of Sheba. |

Hetty, the Queen of Sheba "Carnival", Oberammergau, Germany, 1954 |

|

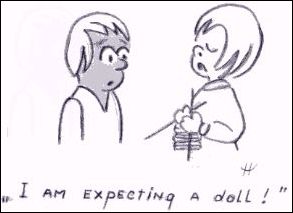

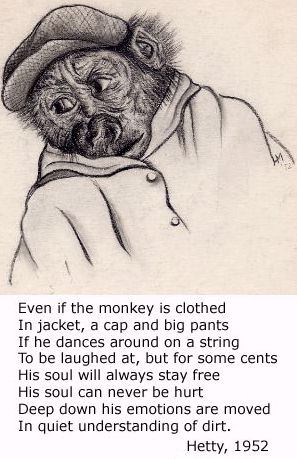

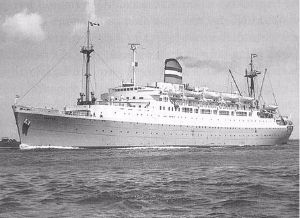

Born in 1921 on the island of Java, Indonesia -- then known as the Dutch East Indies -- Hetty had the idyllic childhood of those fortunate enough to be born into colonial life in the tropics. Every few years the family would board a ship for the Netherlands and enjoy a 3-month vacation -- visiting relatives in the home country, skiing in the Swiss Alps, and sunning on the French Riviera. In early 1939, on one such furlough, Hetty decided to remain behind in Holland with her older sister Jannie, who had returned there a year earlier to go to school. Her parents were concerned about growing rumors of war, but the Dutch government had reassured them that the Netherlands was not in danger and, despite dark forebodings, they and younger sister, Robbie, returned to the East Indies, leaving Hetty in the care of her sister. After a sheltered childhood, Hetty had gained her independence. While attending huishoudschool (household school) -- where she learned, I gather, how to cook real Dutch food, iron shirts, and sew buttons -- war breaks out and Hetty suddenly finds herself living in an occupied country. At first things aren't too bad. The two sisters are still able to exchange letters with their parents in the East Indies, but then that part of the world is invaded by the Japanese and all contact is lost. Worse, when her sister Jannie loses her life while choking on a peanut, she's suddenly on her own for the first time in her life. At first, Hetty tries to deal with her grief by training as a nurse (unsuccesfully, she kept fainting at the sight of blood), but then famine hits the country and she runs out resources. A friend urges her to join the Dutch resistance -- not only to help others in need, but herself -- smuggling food from the farms into the city and falsifying identity papers, all the while wondering if her parents and sister Robbie are still alive. They were -- but only barely. When the war draws to an end, Hetty marries her boyfriend, Jack. Soon after she receives word that her parents and sister have been located in Batavia (now Jakarta), awaiting a ship to be evacuated back to the Netherlands. They had spent the previous four years in segregated concentration camps and her father's captivity had been devastating to his health. But they were alive! Six months later, in the late spring of 1946, Hetty and her family are finally reunited when the evacuee ship sails up the Amstel river and docks in the port of Amsterdam. The earliest memories of my mother are the jokes she used to tell my brother and I. Looking back they weren't particularly funny, but they were in the way she told them. Many of her jokes involved the same two characters: Sam and Moe. For example, Sam and Moe, brave soldiers in the war, were sitting in a trench, bullets flying all around them. Sam turns to Moe: Sam: Moe, does blood smell like poop?Moe: I don't thnk so. Sam: Good. Then I'm not hurt. Another has Moe coming home to find Sam stark-naked except for his customary bow tie: Moe: Sam, why are you naked?Sam: I'm not expecting any visitors. Moe: But why the tie? Sam: Well, you never know. She also related the funny things we said when we were younger, although I have no idea whether they were true. Son: When I grow up I want to marry Betty.Pa: You'll have to wait a long time. Marriage costs money. Son: Oh, I'll earn enough money. Pa: Yes, but when you get children, it'll cost a fortune. Son: I won't have children. Pa: You don't know that. Son: Sure I do. As soon as she lays an egg, I'll step on it. Son: I scraped my knee in school and the teacher wouldn't kiss it better. Ma: Teachers don't do that. Only mothers do. Son: How can I make her a mother? She would often illustrate her jokes. They are the earliest cartoons I remember. Her passion for drawing eventually turned into a life career of various art forms. In fact, she turned everything into art or a craft of some sort. Unless it was a serious health hazard, she wouldn't throw anything away. Burned matches became an intricate mosaic on a cigar box or table top. She did the same with bottle caps, twigs, pebbles -- nothing was wasted. Her first love, though, was painting. In the post-war days, when she couldn't affort paintbrushes (or perhaps they weren't available), she painted with her fingers or an old toothbrush. Her style was surrealism, not exactly the pretty pictures you'd hang on your livingroom wall, but in the early fifties she caught the attention of wealthy art collector Herbert Jochems. I recall that he looked like a bum, wearing a sweater that was about to unravel and a 3-day growth of whiskers that would look chic today, driving an old Studebaker, and he rarely spoke -- a Dutch version of Howard Hughes in his later years. But he bought her work and even exhibited some of her work at a gallery in Paris. In the early sixties, my father and mother got divorced and Hetty decided to move to Canada and take us along. Great idea, I thought, but with no friends and relatives there, no job offers, and only about $800 in our name, I had no idea what we were going to do in Canada. I don't think she did either. Perhaps the street were paved with gold, just like in America. At the time, the Dutch government had a program that subsidized ship's passage for emigrants to move to Canada (perhaps as a gesture of goodwill to Canada, a country in need of talented immigrant workers). So on May 23rd, 1963, after waving farewell to our tearfull friends and relatives on the pier in Rotterdam (they thought we were nuts but we did sense some envy), our emigrant ship, the ss Rijndam, sailed out to open sea. Five days later we were officially landed as immigrants to Canada at the port of Montreal, Quebec. The first thing we noticed was that we were overdressed (my brother and I were both wearing neckties). Montreal is a great city but we quickly decided that this was not the place where we wanted to settle (no cowboys!). We did get a chance to visit an Indian reservation but were disappointed that the little totem poles were made in Japan. So we took the train all the way across the country to Vancouver, where Hetty landed a job in a bakery putting toppings on pastries in the middle of the night while my brother and I scoured the help-wanted ads for a more lucrative career (or a gold-paved street). Always inventive, Hetty had obtained the key to a long-empty tenement (no electricity, no water) and that became our happy home. Using an old metal coat hanger to toast bread over a candle, she kept up our morale by telling us funny stories. |

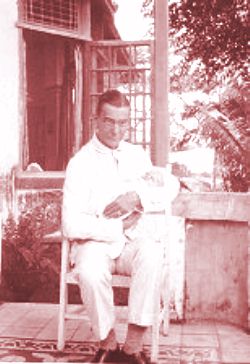

Baby Hetty and her father Tegal, Java, Indonesia, 1921  Hetty (6) and sister Robbie, Indonesia, 1927  Haagse Huishoudschool The Hague, Netherlands, 1940  Hetty, 1945

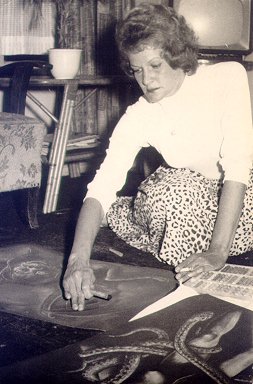

Sons Jaap (4) and Dick (2), 1951    Hetty at Work, 1962  ss Rijndam Rotterdam to Montreal, 1963 |

|

Fortunately this didn't last long. Hetty was too proud (and stubborn) to admit defeat and ask relatives for help to get us back to the Netherlands. The day she got fired from her bakery job for falling asleep over the pastries, we found an ad for a housekeeper on a 500-acre ranch in the Cariboo in the interior of British Columbia. Free room and board for all three of us, but no pay. Oh well, we figured that my brother and I could earn some money by doing odd jobs. At least we had a place to stay and free food. The ranch was in Lone Bute and as the name implied, it's in the middle of nowhere and it took all day on the bus to get there. And then another two hours for the old rancher (we figured him to be in his seventies) to get us from the bus stop to the old ranch house in his old pickup truck, over unpaved roads. When we arrived we learned that the rancher lived alone and the place had no running electricty. Just like the other place, my brother said wryly. It did have a generator but were told that it would be shut down at 7 every night. The rules of the house were simple: (1) Hetty was to get up at dawn, fire up the cooking stove and make breakfast, followed by other various housekeeping chores. (2) The boys (my brother and I) have to work for their food. Despite Hetty's protests, the man wouldn't budge. He had us over a barrel. On the positive side, my brother and I were given a car, a 1947 Ford Austin, if we could get it started. We had never driven a car before, had no license to do so, but it seemed to matter little in that part of the world. Also, we finally had a fixed abode and could contact friends and relatives back home to inform them of our good fortune. We lasted most of the summer there. Cowboy life quickly wore thin. On sundays, the hangman (Hetty had dubbed him so) would take us into town where we had a chance to pick up a Vancouver Sun newspaper and scour the help-wanteds again. The problem was how were we going to get out of here and back to the civilized world? Hetty applied for another housekeeping job in Qualicum Beach on Vancouver Island and after some correspondence, she decided to accept the offer. With pay this time. A neighboring rancher had taken pity on us and agreed to take us back to Vancouver in his cattle truck -- Hetty in the cab and my brother and I in the cattle compartment (without cattle). From Vancouver, we took a ferry across to Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, not knowing what to expect. Little did Hetty know that she was about to meet her new husband, Douglas T. Fredrickson. |

|

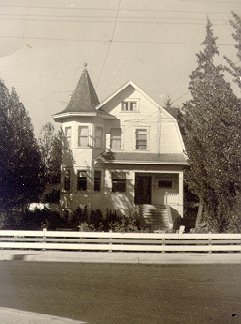

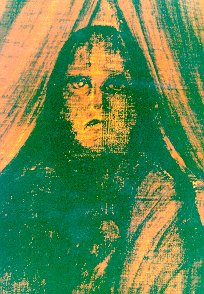

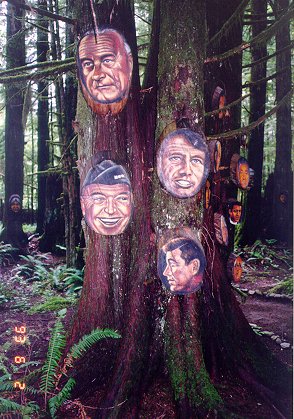

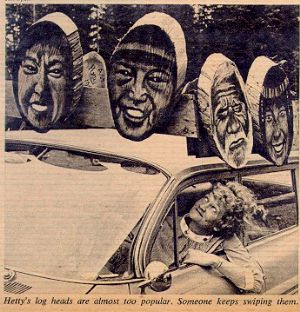

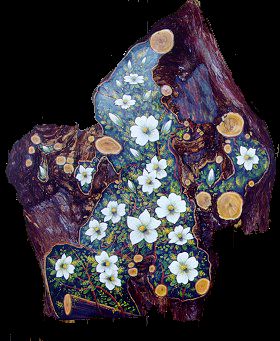

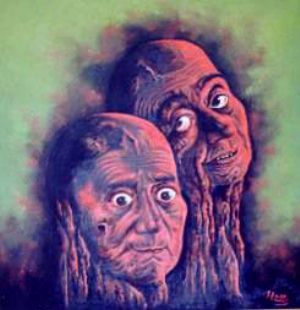

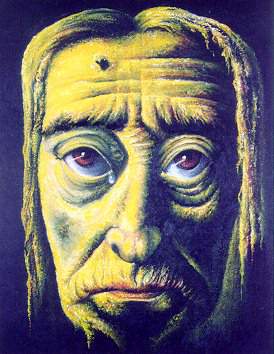

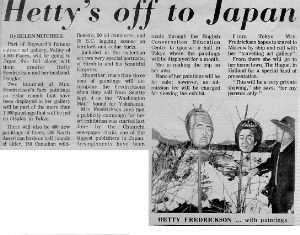

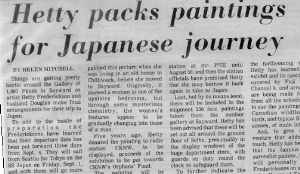

Fortunately, the night before we had spent at a motel and we'd had a chance to clean up and put on our 'finest clothes' in the morning. We looked spiffy. Douglas T. Fredrickson was as surprised by us as we were by him when he met us at the ferry terminal for the first time. The man was a delight -- bursting with positive energy and good humor. We learned that he was a logger (the kind that falls trees), divorced, and had been caring for his three children on his own. Thus the need for a housekeeper. This was a major turning point in Hetty's life, the beginning of many years of happiness and fullfilment in Canada. After she and Douglas were married in 1964, she blossomed and began painting again. In 1966 (I had moved to Japan), Hetty and Douglas moved to the town of Chilliwack in the Fraser Valley where they bought an old 14-room mansion with a turret on top. It looked like a castle and immediately appealed to Hetty. Shortly after they had settled in, strange things started to happen. Footsteps were heard going up the stairs and walking around in one of the empty bedrooms on the top floor. The room was furnished with an old iron bed and a chest of drawers and from it they heard noises that sounded like furniture being moved. Hetty started to have a recurring nightmare. She found herself in the hall on the top floor, looking down on a little, mummified woman, dressed in in red and yellow housecoat. The woman had her arms raised and partly covered her head as if she was terrified. A strong wind was blowing big pieces of dust around. Jokes were made about a possible ghost, but when the footsteps became louder and doors started to open without assistance, Hetty inquired in town about the history of the house. She found out that the house had been built in 1912, and that no blueprint existed. Many people had lived in it and it was impossible to trace a woman in a red housecoat. In a period of 10 years, two men committed suicide in the house, but respect for their families kept her from delving into details. All these facts, however, did not explain the uncanny details. Another story about a woman, who was supposed to have been killed in the house and then cemented in the chimney, was more interesting, but this was never proved to be true. Trying to get proof for a thing that seemed utterly unbelievable, Hetty decided to make a painting of the ghost, with the idea that if it was causing the disturbances and moving the furniture, it certainly would move its own portrait. She sat in the so-called room for many evenings, hoping the furniture would move in her presence, and to get the right inspiration. She finally painted a huge canvas with a ghost-like figure in the center and a face based on the appearance in her dreams. She placed the painting next to the bed and chest of drawers, and from then on she checked its position every day. The painting never moved an inch, and Hetty started to lose interest in her experiment. After a couple of weeks, showing the painting to some of her art students, she noticed a light difference in the features of "her" ghost. Sure that her own imagination was to blame for this, she made no remark to anyone about the change. But, as the days went by, she could not deny the fact that the painting was changing. The right side of the face, which she had left dark, to make it more mysterious looking, started to shape up. The expression of fear had disappeared and the apparition was definitely more male than female. And everyone who had seen the painting it the beginning, noticed the changes. Hetty was not one to shy away from publicity, but what happened next, she was not prepared for. News media and curiosity seekers started to haunt the house and word of the changing "ghost painting" spread like wildfire. Thousands of people walked in the driveway, trying to get a peek at the ghost, while letters and telephone calls made a normal life impossible. Hetty was still trying to investigate the delicate matter, and found a little room in the turret, which was supposed to be just an ornament. She was shocked at first to see the same pieces of dust from her dream on the floor, but it turned out to be deteriorated insulation. The room was empty. She also found a boarded up laundry chute, going from the top floor to the kitchen. It contained nothing but cobwebs. When she was about to tear down walls and look for a body in a cemented chimney, Douglas had enough and forbid this costly experiment. A professor from the University of British Columbia (a member of the British Society of Psychic Research), who had stayed in the house for several days, also advised to leave the chimney untouched. The eventual find of a dead body would supply no proof and would only cause more publicity. With all the attention it had become impossible to live in the big, beautiful house in peace. Douglas had accepted a job offer back on Vancouver Island. As a logger he often spent weeks at a time in logging camps away from home and the idea of living alone for weeks in the haunted house no longer appealed to Hetty. She decided to go to Holland for a much-needed break and visit her parents. She took the ghost painting with her and arranged an interview with the famous professor in parapsychology, Dr. Ten Haaff. Although Dr. Haaff had no doubts about the extraordinary spiritual influences in this case, he could shed no further light on the matter. Upon returning to Canada she joined Douglas on Vancouver Island; they would let the Chilliwack house stand empty for now and decide what to do with it later. Eventually, it was rented out for a couple of years, then sold, and finally, it burned to the ground, taking its secrets with it. In the meantime, Hetty had many proposals of sale for the painting, but she could not bring herself to sell it. When she was approached by a Vancouver radio station that wanted to buy the "ghost" and make money for their orphanage fund, Hetty suddenly had the answer. She donated the painting to the orphans. "The Ghost of the House in Chilliwack" would be the first ghost in history to contribute to charity! The last time Hetty saw the painting, it looked old and threatening, but it had made a lot of money for parentless children. Hopefully, its last expression will be one of peace. The logging industry was booming in the northern half of Vancouver Island. In 1967, Hetty and Douglas rented a house in the village of Sayward, a small logging community, about 45 miles north of Campbell River, Salmon Capital of the World, intending to stay for only one year. Because there was not much to do for children, Hetty decided to organize a paint-in for them. To avoid the high cost of canvas and oil paints, she asked Douglas to cut the butt ends of logs and she would get exterior house paint, so the children could create to their hearts content. When Douglas came home with the slabs, Hetty could see a face in each piece of wood and started to experiment with the new medium. She painted 10 faces, and Douglas nailed these on the trees alongside the logging road to inspire the children during the event. Next day, however, all 10 paintings had disappeared. Angry and disappointed, Hetty painted 10 others, but the same thing happened again. After the paint-in was over, she created 100 new faces, and Douglas fastened these on the trees alongside the highway. This time the paintings turned out to be traffic stoppers and caused a traffic hazard. Before they had all disappeared with their unlawful owners, they decided to take the last ones down and auction these off to start a fund for a new recreation hall. With determination, Hetty started to paint 10 new faces, this time on plywood of six by four feet. To avoid any thievery, Douglas fastened these giant paintings, with belt and spurs, 40 feet above ground level on the trees alongside the highway to Campbell River. But, within two weeks, only one face was left to cheer up the road, and nobody ever found out where the others went. However, everything has a good side, and sparked the creation of "The Valley of a Thousand Faces." Hetty and Douglas bought 4 acres of park-like forest bordering the highway and the White River, just outside the village, and fenced it off. Douglas, armed with a power saw, and Hetty, buried in wood and paints, set out to work. After a year of "sixteen hours a day" and with the help of Dick, who had come back from Holland where he was studying art, she finished a thousand different faces, depicting well-know people, little stories and events, and all races of the world. Douglas then created a winding footpath through the park, consisting of 1500 cedar slabs. The faces were arranged, laid out, and fastened to the trees. The forest was kept in its natural state and formed a perfect background for the original exhibit. When it was all done, the result of what they had created surprised even Hetty and Douglas -- the al fresco art gallery in the forest was striking in its natural setting and they both knew that they had found their permanent home. (A trailer moved to the property served as their temporary home, which would later be convered into an indoor gallery for Hetty's canvas oil paintings and other works of art that needed to be protected from the outside elements. The "outdoor" faces were done in exterior house paint, just like the originals, and they "aged" well in inclement weather.) In May of 1969, Hetty and Douglas officially opened "The Valley of a Thousand Faces." Attendance that first day was modest with only a few local dignitaries and some curious villagers. After all, Sayward was not exactly on the "beaten path," hundreds of miles from such big cities as Vancouver and Victoria. However, it didn't take long for word to spread about the unusual exhibit and the number of visitors grew rapidly, and from further away. (Several years later, Hetty was stunned when she received word that Roy Disney (brother of Walt) was coming up from California to take a look.) From the day it opened until the day it closed in the year when Hetty passed away (1994), admission to the park was kept at $1 per adult. Children were free. Although none of the faces in the park itself were for sale, the main source of income came from the sale of Hetty's other paintings -- done in oil on both canvas and wood, and more suitable for display indoors. (TO BE CONTINUED, shortly I hope.)Return to Main Page |

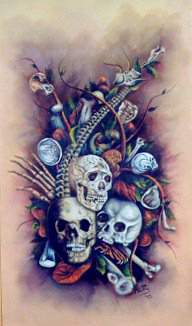

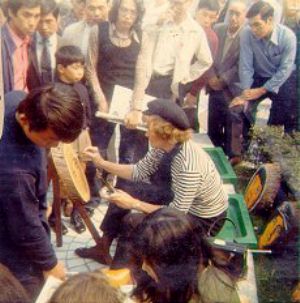

Haunted House Chilliwack, BC, 1966  Ghost Painting Chilliwack, BC, 1966  Ghost Painting Chilliwack, BC, 1966  Vancouver Sun, 1966  Vancouver Sun, 1966  Vancouver Province, 1966  Vancouver Sun, 1966  Vancouver Sun, 1966  Vancouver Province, 1966  Japanese magazine article  Japanese magazine article  Hetty at Work  Hetty and Douglas in their Valley of 1000 Faces  Valley of 1000 Faces  Valley of 1000 Faces  Hetty's station wagon  Hetty and her many faces  A surprise visitor - Roy Disney (L)  John and Elvis painted on cedar  Faces painted on cedar  Valley of 1000 Faces  Painting on cedar burl  Painting on cedar burl  "Million Dollar Painting" - Hetty's favorite painting Oil on canvas  The Lovers - Oil on canvas  Bouquet of Death - Oil on canvas  Regret - Oil on canvas  Symphony in Alcohol - (done with bottlecaps)  Hetty's Japan Tour  Hetty's Japan Tour  Hetty's Japan Tour  Hetty painting in Tokyo  Hetty on Japanese TV (11PM Show - NTV) |